Author Blog

This is where I share my research into the world of Jane Austen, chat about other writers, and explore the craft of writing in general.

If you have any comments or questions, please don't hesitate to reach out!

Honour and Obedience

Life was hard for men in the British Navy during Jane Austen’s lifetime, especially for the lower ranks. Demand for sailors grew dramatically in the 1790s because of the French Revolutionary Wars, and to make up the numbers, press-gangs took people against their will. They waited outside public houses in dockside towns for merry revellers to come out from an evening of drinking, then put them aboard a boat.

These Press Gangs were run by the Royal Navy Impress Service, which was an official organisation responsible for compulsory recruitment. It was usually headed by a lieutenant overseeing a ‘band of thugs’, dispatched from a warship anchored offshore. Tens of thousands of crew members were recruited in this way.

Unsurprisingly, these recruits were not happy to find themselves involuntarily aboard a ship with no way of reaching land, and their commanders feared an uprising. Discipline was strict to keep them in order, and punishments were severe.

When Charles Austen headed the HMS Namur between 1811 and 1814, his log included some of the punishments he oversaw. The most common punishment was flogging, applied for any number of reasons, such as mutinous language, disobeying orders, theft, violence, drunkenness or riotous behaviour. All of these earned a public flogging in front of the rest of the crew.

Photos: HMS Victory, Portsmouth Historic Dockyards

Charles recorded in January 1813:

- John Bailey – 36 lashes for theft

- James Taylor – 24 lashes for theft

- John Blinkensop – 24 lashes for theft

A separate entry records 36 lashes for one crew member attempting to stab another.

Lashes were administered by a special stick known as the Cat o’ Nine Tails (or the ‘Cat’). This was a short stick with nine strands of knotted rope, each strand being two feet long. The victims were stripped to the waist and secured to a grating where they would cry out in agony until their lashes were done. The spectacle could only be stopped if the attending surgeon intervened.

A more severe punishment was ‘flogging around the fleet’, whereby the victim was tied to the bars of a ship’s launch boat and then rowed from one vessel to another in the vicinity. A drummer would accompany them, playing 'The Rogue’s March' to signify the disgrace of the sailor.

One recording of such an event on the Namur was on 5th March 1813. The victim was John Crossley, brought onboard from the Starling, to receive 200 lashes for deserting his post. A further 100 lashes were administered on board other naval vessels anchored nearby.

Christmas was a time of brief forgiveness for Charles Austen, and he pardoned a dozen officers and removed their punishments, ‘in honour of the day’

Frank Austen saw his share of punishments, too. In the book ‘Jane Austen’s Sailor Brothers’ (written by Frank’s grandson and great-granddaughter), there is a list of some of the punishments on the vessels that Frank served on.

Later, there are reports that one midshipman was court-martialled for robbing a Portuguese boat and sentenced ‘to be turned before the mast’. This meant he would have lost his rank and privileges and be demoted to the lower ranks. He would be deeply humiliated in front of the entire ship’s company by being stripped on the quarter deck and then having his head shaved.

This punishment derives its name from the living quarters onboard, as on a warship, officers and petty officers lived towards the back of the ship in the quarterdeck. Ordinary seamen lived towards the front - before the mast - in the most cramped and roughest part. So, being ‘turned before the mast’ meant being turned away from your place at the back of the ship and forced to go to the front: losing your living space, your authority, and your rank.

Executions happened, too, on ships, with 6 executions recorded in the log book of HMS London, for mutiny.

Further reading on naval punishments can be found in an article written by Jay Hemmings for War History Online. You can read it here.

Henry Austen was not a sailor, but a soldier in the army. He also witnessed a public execution with his regiment, the Oxfordshire Militia.

Worried about unrest in England following the removal of the French King just across the channel in the French Revolution, the British army was quick to crack down on any lawbreakers. During the summer of 1795, there was a desperate shortage of food in rural towns and extortionate prices were charged for basic provisions. Food riots were commonplace, and, seeing severe starvation in the course of their duties, some of the soldiers decided to act. They took over some bread and flour facilities in a town in a ‘disorderly manner’ and sold them to locals at more reasonable prices. This was treated as a mutiny by their superiors, who ensured that the ringleaders were arrested. Four of the soldiers were flogged, but two of them were brought before a firing squad in Brighton. Henry Austen was studying at Oxford University at the time, but like every other member of his regiment, he was ordered to return to barracks and watch the shooting, which took place on 13 June 1795. This was a strong and memorable lesson that no form of insubordination would be tolerated.

You can learn more about this event on the Brighton Museums website here.

Photos: Jane Austen Festival, Bath, 2024

circulating libraries

Circulating libraries in Jane Austen’s time operated a little differently from the way we use them today. It’s easy to think of them like the mobile library vans we see serving rural communities, but in fact, the term ‘circulating’ refers to the books moving around among readers, rather than the library itself.

Photo: The old circulating library in Milsom Street, Bath

A circulating library was generally a large room in a building in town, with labelled shelves listing categories such as sermons, theology, history, travel and novels. Ladies and gentlemen came in to ask for the title they wanted, and men wearing white wigs would climb up and down ladders to retrieve the request. There was no whispering hush that we have come to associate with libraries nowadays, and the visits were seen more as social occasions, offering the chance to exchange news with a neighbour.

Someone would serve on the front desk, checking that any books being returned were not overdue or damaged, as even turned-over page corners were frowned upon, and a fine was issued.

Librarians would recognise their clients, and in smaller villages, the library may be no more than a room inside someone’s house. Sometimes they were combined with shops where a few shelves were put aside within a milliner’s store or a food supplier. Although it was more work for them and did not bring in profits, having a shelf of books did serve to encourage more customers inside, who may then leave with a strategically positioned purchase on the way out.

In larger cities and seaside resorts, the buildings were bigger, often with a reading room where people would settle down for a few hours and read the daily newspapers.

It was not common practise for customers to browse the shelves themselves, but usually the subscriber would tell the clerk at the counter the name of the book they wished to borrow, and their subscriber number, which would be recorded in the ledger. If it were a novel printed in many volumes, they would also need to specify which volume they wanted. The librarian would ask the clerk to find it for him and bring it down so that he could present it to the customer. On busy days, subscribers would chat with friends or read a magazine in the reading room while they waited.

There was no blurb on the back of the books as they were all bound in either cardboard or vellum. Recommendations from friends, or knowledge of an author’s previous works, went a long way to help a reader choose what to take next, as did advertisements from printers and booksellers that regularly appeared in newspapers. If the work were from a new author, or a name they were not familiar with, a meticulous subscriber may spend a little time reading an extract before committing to borrowing it, and if they did not like it, they would hand it back and ask for something else. Library clerks were aware of what was popular and made recommendations if necessary.

Photo: Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire

To subscribe to a circulating library, borrowers had to pay a fee. Depending on how big the library was, and where it was located, fees may be charged annually, quarterly or as and when a book was borrowed. There were also different levels of privilege in borrowing, depending on which class of membership someone wanted to pay. Most circulating libraries would provide catalogues with the titles of the books available in their establishments, and if a particular title was already out with someone else, then the customer would go on a waiting list and be informed when it was back in stock.

If you would like to learn more about circulating libraries and also the ones that Jane Austen used, you will find some interesting links below:

This link here takes you to an article on the Jane Austen's Regency World website, and this link here takes you to the Random Bits of Fascination website, where you will find a series of articles on the topic.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

In 1812, Jane Austen’s first novel, Sense and Sensibility, was selling well, and she was ready to publish her second. This was First Impressions, a work she had originally written in 1797 when she was living in Steventon rectory. Now at her cottage in Chawton, Jane had finished her edits and was happy for it to go to print; the trouble being that since she had written her first draft, another author had since released a book using the same title.

Margaret Holford was the author in question - a poet and novelist who wrote in the fashionable sentimental genre of the day, similar to that of other contemporary female novelists like Frances Burney and Charlotte Smith. There were gothic settings and melodramatic characters.

This annoying occurrence meant that Jane Austen was forced to think of something new and appropriate to capture her own love story between Mr Darcy and Miss Bennet.

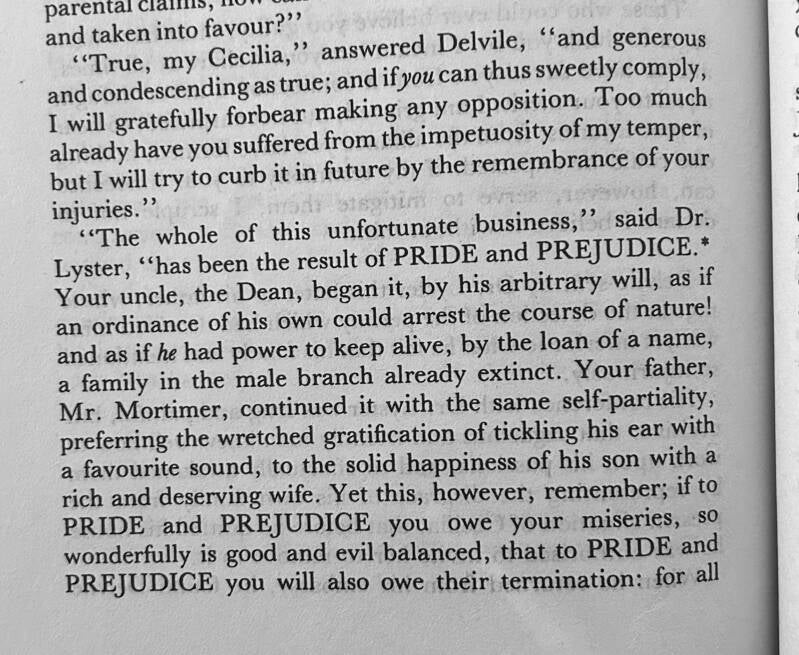

The Austen family were big fans of Frances Burney, and in Volume 5 of Burney's novel, Cecilia, the words PRIDE and PREJUDICE are repeated three times in quick succession. What's more, they jump off the page because they are in capital letters and are what many historians believe prompted Jane to choose those words for her work.

Margaret Holford’s First Impressions did not stand the test of time like Pride and Prejudice did and today it is rare to find an original copy outside of a research library. You can, however, read a replica of Volume 1 as part of The Corvey Collection of European Literature 1790 to 1840 if you are interested, available on Amazon here.

There is no confirmation in any of Jane Austen’s letters of what caused her to choose Pride and Prejudice as her definitive new title at the time, but the Austen family’s fondness for Ms Burney’s works must surely make this scenario more than a mere coincidence.

Royal Acclaim for 'sense and Sensibility'.

A fascinating fact was recently discovered regarding one of the first purchasers of Sense and Sensibility. As detailed in the blog post below, the initial advertisement for Jane Austen’s debut novel appeared in The Star newspaper on October 30th, 1811, followed the next day in The Morning Chronicle, listed amongst ‘BOOKS PUBLISHED THIS DAY’ by Thomas Egerton.

One would expect from this that the initial sales would begin during the first week of November, but in 2018, a doctoral student working for the Royal Archives made the discovery that two days before the first advertisement appeared, the Prince Regent (future King George IV) already had a copy of 'Sense and Sensibility' in his royal palace.

Photo: King George IV, Wikipedia, Public Domain

A receipt for the sale clearly states that it was purchased on the 28th October, meaning that Mr Egerton must have kept the prince abreast of all his new releases before they hit the shelves.

Image from Georgian Papers Programme Blog (link below)

What an honour for an unknown author.

Of course, Jane Austen would never have known about this transaction, nor how successful Sense and Sensibility would become, but knowing now that the heir to the English throne was one of her first readers, we can see where his lifelong admiration of her writing began.

Photo: Princess Charlotte, Wikipedia, Public Domain

It was not only the prince who admired her work: his daughter, Princess Charlotte, praised the novel to a friend in a private letter a couple of months later:

“Sense and Sensibility I have just finished reading; it certainly is interesting, & you feel quite one of the company. I think Maryanne & me are very like in disposition, that certainly I am not so good, the same imprudence, &c, however, remain very like.”

This defining discovery serves as a subtle reminder to any writer that you never know who will read your book, or how influential they might be!

If you would like to learn more about the Royal Archive discovery, it is detailed in the blog post 'Jane Austen and the Prince Regent: The Very First Purchase of an Austen Novel' written by Nicholas Foretek, of the University of Pennsylvania, who was the Research Fellow to find it. You can read it here.

'in boards'

The first advertisement for Jane Austen’s debut novel, Sense and Sensibility, appeared in 'The Star' newspaper on 30th October, 1811 and was followed the next day with a duplicate ad in 'The Morning Chronicle'.

It read:

‘In 3 vols. price 15s in boards, a New Novel called

SENSE and SENSIBILITY. By Lady –

Published by T. Egerton, Whitehall; and may be had

Every Bookseller in the United Kingdom.’

The term "in boards" referred to a temporary book binding using plain board covers to protect the printed pages. Most 18th-century books were sold in this way by the printer or the bookseller, in the form of loose printed sheets or in simple, fragile paper wrappers. The buyer would then take the work to a professional bookbinder who would bind it according to the customer’s personal specification.

Photo: Lacock Abbey, Chippenham

Often this matched the same design as the other books on their bookshelves, and would account for why many library displays in historical houses today have rows of books in the same colour.

Photo: Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth

Like any consumable good, book binders offered different patterns and materials to suit different budgets and tastes and they could be an expensive purchase. Therefore, "in boards" refers to that temporary stage when the books were not yet finalised, but covered in a thick blue-grey cardboard known as a binder's board. This was of minimal durability and not meant for long-term use, but it did mean that the book could still be read before being sent away for its final coating of leather or vellum.

This economical practice was popular and widely available until the 1820s, when permanent bindings became standard practice from the time of purchase. Any surviving 18th-century book found today still "in boards" is a very rare find.

A student from West Dean College undertook the conservation of such a binding and documented their progress in a blog post. Click here if you would like to learn more.

one degree of separation

William Cowper was one of Jane Austen’s favourite poets. Her familiarity with his work is evidenced in her letter to Cassandra in November 1798. She mentions a sum of money “… is to be laid out in the purchase of Cowper’s works.” The following month, she reveals, “My father reads Cowper to us in the morning, to which I listen when I can.”

In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price talks about Cowper’s, The Task, and in Sense and Sensibility, Marianne Dashwood judges her suitors by how passionately they are moved by his poetry: “Nay, mama, if he is not to be animated by Cowper!”

William Cowper was born in November 1731 in Hertfordshire, England, and after studying at Westminster School, he trained to be a lawyer. Unfortunately, he suffered from frequent bouts of depression and attempted suicide. Whilst in recovery, he became an Evangelical Christian and devoted himself to writing poetry. His works celebrated nature and domestic life, often laced with themes of moral reflection. He was a determined abolitionist too, and he became an inspiration to the Romantic poets, Wordsworth and Coleridge.

You can read his biography and complete works on Project Gutenberg, here.

Photo image taken from Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47790/47790-h/47790-h.htm

Despite his creativity, however, he never felt truly at peace and continued to battle melancholia and religious despair all his life. He died in April, 1800, aged 68.

In 1785, his collection of poetry The task: A Poem, in Six Books was released (as referenced by Fanny Price in Mansfield Park.) Amongst the collection was a title: ‘An epistle to Joseph Hill, Esq.’

This was a poem about friendship and how, despite the passage of time, some friendships still hold a deep connection. For William Cowper, Joseph Hill was a person of great integrity whom he admired and felt honoured to call a friend.

Joseph Hill was a lawyer, and the two men had met when they were training together. When Cowper gave up that career to focus on poetry, Joseph Hill looked after some of his finances. Some handwritten letters between the two men still remain today, fetching substantial sums of money at auction. Read more here.

So how does this relate to Jane Austen?

Well, in 1806, the Honorable Mary Leigh of Stoneleigh Abbey died, leaving behind a large legacy and a complicated will. Several members of the Leigh family laid claim to it, including Mrs Austen's brother, James Leigh-Perrot.

The negotiations around who should benefit from Hon. Mary Leigh’s vast fortune were tense and in the end, the estate passed to the Reverend Thomas Leigh, who was Mrs Austen's cousin. The lawyer appointed to oversee the administration of the will was the very same Joseph Hill.

Photo: Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire

When Mrs Austen, Jane and Cassandra arrived at Adlestrop to call upon Rev. Leigh in August 1806, their stay coincided with the need to sort out these legal affairs. The kind Rev. Leigh took the ladies with him back to Stoneleigh Abbey, where they remained for nine days. Travelling with them in the same party was Mr Hill, and he remained in their company for the nine days that they were there.

It is not beyond the realms of possibility that Mr Hill’s connection to William Cowper would have been revealed during this time, especially considering that literature and poetry were frequent and safe topics of conversation amongst dinner guests and strangers.

How exciting it must have been for Jane to speak to someone who had a personal acquaintance with the poet she admired. I wonder what she asked?

Photo: Stoneleigh Abbey, Warwickshire

If you would like to read Cowper’s poem ‘An Epistle to Joseph Hill, Esq’ in full, you can read it here on the englishverse.com website, here.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Coopers

Jane Austen often used names as working titles for her novels, such as The Watsons or Elinor and Marianne. If she had applied this practice to write about her own relations, then I venture that The Coopers would have made a fascinating read too. The Cooper family were Jane’s aunt, uncle and two cousins, and together they build a classic generational saga.

Their story begins with Jane Leigh, born in 1736 in the village of Harpsden, near Henley-on-Thames. Her father was rector of St Margaret of Antioch Church and Jane had an older brother, James; a younger sister, Cassandra; and a baby brother, Thomas.

St Margaret of Antioch Church, Harpsden.

Thomas was named after his rich uncle, Thomas Perrot, who owned the prestigious family seat of Northleigh. Having no children of his own, he passed this estate onto Jane Leigh’s elder brother, James, in his will, stipulating that the boy must assume the name Perrot when he inherited. Thus, the young man grew up to become James Leigh-Perrot.

Baby Thomas was not a well child and suffered from fits. He was sent to the country to be fostered by Mr and Mrs Cullum of Monk Sherborne, where he remained on their family farm for the rest of his life, reaching the impressive age of 74. In later years, Thomas was to be joined by another young boy who had similar developmental difficulties. This was his nephew, George, (Jane Austen’s brother) who also lived out a long life there.

When Jane Leigh was 26, her father announced his retirement, and the family moved to Bath. Sadly, Mr Leigh died in the city less than two years later, and a few months after that in April 1794, Jane Leigh and James Leigh-Perrot witnessed their sister Cassandra’s wedding to Reverend George Austen from Steventon. In December 1768, Jane Leigh herself got married to Rev Dr Edward Cooper, rector of Buckland St Mary in Somerset.

The Coopers' house on Royal Crescent, Bath

Initially, the newly wedded Mr and Mrs Cooper lived in Reading with Rev Dr Cooper’s mother. They welcomed two children in quick succession, a son called Edward, and a daughter called Jane. But when Rev Dr Cooper’s mother died, they returned to Bath. Using the money from his mother’s inheritance, Rev Dr Cooper bought a fashionable house on the brand-new Royal Crescent. They moved in during the last quarter of 1771 when only thirteen houses were standing in this new development. Modern records list this property today as number 12.

Nine years later they moved again to a larger house on Bennett Street, close to the Upper Assembly Rooms. Things were going well for them and in 1782, Rev Dr Cooper was given the living of St Mary the Virgin in Whaddon, a few miles south of Bath.

Rev Dr Cooper had a widowed sister named Mrs Cawley. In 1783 she opened a school for girls near Oxford, where her late husband had been Principal of Brasenose College. Twelve-year old Jane Cooper was enrolled to study there, accompanied by her cousins, Cassandra and Jane Austen, as classmates. Over the summer, a measles outbreak hit Oxford, so Mrs Cawley moved her girls to Southampton for safety. This turned out to be a bad decision, as Southampton was rife with typhus fever. All the girls caught it, and Jane Cooper summoned her mother to come and help them. Mrs Cooper and Mrs Austen wasted no time in travelling to Southampton to bring their daughters home.

As rescue missions went, it was successful in as much as all three girls recovered. The tragedy came when Mrs Cooper contracted typhus herself and died a few days after getting home to Bath. She was buried in her husband’s churchyard at Whaddon.

Rev Dr Cooper was heartbroken and could no longer bear to live in the city. He moved to Sonning in Berkshire where he became rector of St Andrew’s Church. Edward Cooper was sent to boarding school at Eton, and Jane Cooper was sent to the Reading Ladies School. For a brief time, Cassandra and Jane Austen joined their cousin again to study together, but they did not stay for long. Jane Cooper remained there and completed her education.

St Mary's Church, Whaddon

St Andrew's Church, Sonning.

During the school holidays, Edward and Jane Cooper were frequent guests in the Austen’s home and were close to all their Austen cousins. Edward Cooper followed in his father’s footsteps to become a clergyman and went to Oxford to obtain his degree where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in the summer of 1792.

Marking the end of his studies, Edward and Jane accompanied their father on holiday to the Isle of Wight. Their close family friends, Mr and Mrs Lybbe Powys and their daughter, Caroline, went with them. One day, they dined with a lady called Mrs. Williams whose son was a captain in the Royal Navy. Jane Cooper was smitten and by the end of the holiday she and Captain Williams were engaged.

The wedding was arranged for later that year, before Captain Williams sailed away to sea, but tragedy struck the family once more when Rev Dr Cooper died upon returning home to Sonning. Jane Cooper’s wedding was postponed, and she went to stay with her aunt and cousins Steventon. Edward remained in Sonning and, with the help of the Lybbe Powys family, sorted out his father’s affairs. Rev Dr Cooper was buried next to his late wife in his former church at Whaddon, where it would be hard to find a more peaceful spot.

Jane Cooper’s wedding eventually took place in December 1792 at Steventon church. The officiate on that day was Tom Fowle, one of Mr Austen’s former pupils from his schoolroom. In a happy sub-plot to this story, some biographers label this event as the time when Tom Fowle became engaged to Cassandra Austen.

St Nicholas Church, Steventon

Jane Cooper’s wedding impacted another member of the Austen family too. Charles Austen was home on leave from the Naval Academy and made a big impression on the naval captain. In his first appointment, Charles was invited to be a midshipman on Captain Williams’ ship and from then on the senior man was an important mentor and patron of Charles’s career.

Edward Cooper married Caroline Lybbe Powys in 1793, and his first church living was the same St Margaret of Antioch in Harpsden that his grandfather had served. The rectory where he and Caroline moved into was the very same house where his late mother had grown up.

Jane Cooper (now Williams) went to live on the Isle of Wight with Captain Williams’ mother, and she and Edward remained very close. When her husband was away at sea, Jane would often stay with him at Harpsden, or Edward and Caroline would visit Jane in Ryde. Captain Williams received a knighthood for his services in battle in 1796, and Jane was granted the title, Lady Williams.

It would be nice to imagine a long and stable life for them now, but tragedy struck once more in 1798. Lady Jane was returning home in her carriage when a frightened run-away horse charged directly at her. She was thrown to the ground and killed, only 28 years old.

St Michael and All Angels in Hamstall Ridware.

Edward Cooper was now the only one of his immediate family left and in 1799 he moved to Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire to take up the living of St Michael and All Angels. He and Caroline raised a large family, although, like many couples, they suffered their own share of infant mortality. Mr and Mrs Lybbe Powys visited them frequently, and Mrs Lybbe Powys kept a diary which can be read today under the title: Passages from the diaries of Mrs. Philip Lybbe Powys of Hardwick house, Oxon : A.D. 1756-1808.

Edward continued to maintain a relationship with his Austen cousins, and they met up from time to time over the years. He was a prolific writer of sermons and published them in a multi-volume collection called: Practical and Familiar Sermons, Designed for Parochial and Domestic Instruction. They were circulated extensively across England and abroad.

Although he remained on good terms with his aunt Austen, it seems that relations between him and his uncle Leigh-Perrot were strained. When Mr Leigh-Perrot died in 1817, there was much speculation as to who would receive a share of his immense wealth. James Austen was the main beneficiary, but Edward Cooper received nothing at all. In a letter to Jane Austen in April, 1817 he wrote: ‘There was probably no reason why I should have expected any distinguished notice in his Will; but I certainly never seriously anticipated the probability of being altogether excluded from it.’ He called it ‘painful’ and assured his cousin that ‘I did not cease to pray for him daily & earnestly.’

Edward remained in Hamstall Ridware until his own death in 1833, aged 62. He was remembered in his obituary as, ‘an able, pious and exemplary pastor, his loss will be long and severely felt by his sorrowing and affectionate people.’

He was buried in St Michaels and All Angels Church in Hamstall Ridware, to be joined a few years later by Caroline. There is a memorial inscription to them both on the east wall of the north aisle, and a family grave plot outside in the churchyard.

Hamstall Ridware Churchyard

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Of No Fixed Abode

Published in 'Jane Austen's Regency World', Sept/Oct 2025

If Mr Austen had not succumbed to a sudden fever at the beginning of 1805, who knows how differently Jane Austen’s life would have turned out? Perhaps she would have found a suitable beau in Bath, like Catherine Morland did in Henry Tilney, and married to secure the family’s fortune.

What actually transpired was different altogether, because when her father died, Jane and her mother and sister lost their home.

Reverend George Austen had been well respected in his Steventon community, but he was never rich. He did not own a large estate and he did not expect to inherit a fortune. When the time came for him to retire, there was no golden nest egg put by.

4 Sydney Place

He moved his wife and daughters to Bath in 1801, and the first lodgings he took were at the top end of his budget. No. 4 Sydney Place was a nicely situated town-house, respectable enough to receive visitors and a pleasant stroll from the centre of town. The first indication that he had over-stretched himself can be gleaned when he gave up the lease early; he had originally signed up to live there for 3 ¼ years (which would have taken him to October 1804) but he forfeited the lease in June.

He did not immediately secure new lodgings for his family either at that time but took them on holiday instead. They spent the summer in Lyme Regis, freeing him from the financial strain of a residence in Bath. The lodgings in Lyme sounded low budget too, with Jane telling her sister in a letter on the 14th September 1804, ‘… nothing certainly can exceed the inconvenience of the Offices, except the general Dirtiness of the House & furniture, & all its’ Inhabitants.’

When the family returned to Bath in October, they moved into No. 3 Green Park Buildings East. This location had been considered once before by Mrs Austen and her two daughters when they first arrived in the city in 1801. They dismissed it then due to its closeness to the river which made the house damp. There were accounts of ‘discontented families & putrid fevers.’

Green Park Buildings

In its favour, Green Park Buildings East did offer spacious accommodation, and the rent was lower than Sydney Place. The neighbourhood was popular with retired clergy and military men, but nevertheless it was in an unfashionable part of town and built on a flood plain. Even with a park view out of the window, the sight could hardly be compared to the grandeur of Sydney Gardens, which they had left behind.

It seems that Mr Austen suffered frequent bouts of ill health when he moved there, evident from Jane’s letter to her brother Frank on 21 January 1805, which announced their father’s death: ‘He was taken ill on Saturday morning, exactly in the same way as heretofore, an oppression in the head with fever, violent tremulousness, & the greatest degree of Feebleness.’ Mr Austen had lived for only twelve weeks in Green Park Buildings before he passed away.

Burial stone of Mr Austen, St Swithin's Church, Bath.

As was the custom of the day, his income immediately ceased upon his death, and no provision was made for his widow. The tithes from his church passed on to his eldest son, James, who took up the living. But the annuity his father had received for his years as a clergyman stopped altogether.

Mr Austen had made provision in his will to leave everything he owned to his wife, but the fact was he did not have much to give; the majority of his goods, furniture and livestock had been auctioned off four years previously when the family had moved from Steventon to Bath.

Mrs Austen had a small income of her own from an inheritance she had been bequeathed some years before, and Cassandra had a small provision from her late fiancé, but Jane had nothing. Fortuitously, an elderly widow whom the girls were acquainted with in Bath died around the same time as Mr Austen and left them both a small sum in her will, but, like Mr Bennet in Pride & Prejudice, Mr Austen had made no allowance that would provide his daughters with long-term financial security.

Unlike Mr Bennett, however, Mr Austen had fathered mainly sons instead of daughters, and this fell in his favour. Society’s expectation at the time was that the males of the family would provide for their women.

The Austens had always been a close family, and the brothers negotiated between themselves what they could afford to give. The newly bereaved ladies stayed on in Green Park Buildings for a few more weeks, then moved out in March to take up temporary lodgings across the city in 25 Gay Street. James summed up his mother’s intentions in a letter to his brother Frank, ‘I believe her summers will be spent in the country amongst her Relations & chiefly I trust among her children – the winters she will pass in comfortable lodgings in Bath.’

25 Gay Street

True to her word, Mrs Austen did just that. In her first year as a widow, she and her daughters went first to stay with Edward in Godmersham, then from there on to Worthing for some sea bathing, concluding with a visit to James and his family in Steventon.

Trim Street

In the spring of 1806, they returned to Bath and moved into lodgings in Trim Street. Whether this was by choice to save money, or necessity as the only house free, we will never know, but it is likely it was only ever meant to be short term. Trim Street was another place they had blatantly rejected, with Jane assuring Cassandra in those early days of house hunting that their mother ‘will do everything in her power to avoid Trim Street.’

Eager to find somewhere more suitable for now, Mrs Austen had her eye on some rooms in St. James’s Square. She was forced to admit defeat soon after when she realised, ‘A person is in treaty for the whole House, so of Course he will be prefer’d to us who want only a part.’

In another twist of fate, a new person was set to join them in their household. Jane and Cassandra’s intimate friend, Martha Lloyd, found herself in a similar predicament to the Austen ladies, having lost her own mother a few weeks after the death of Mr Austen. She would bring her own inheritance as a contributory income which, when put together with the offerings of the brothers, should allow them all to live in reasonable comfort.

By now it was clear that Bath was not meant to be their destiny, and a brighter alternative presented itself. Frank Austen was home on leave from a long voyage with the navy and was getting married. He offered his mother, sisters and Martha a home with him and his wife, Mary, after they were wed. He proposed to rent a large house in Southampton for them all to live, content that his new bride would be safe with his dear sisters and mother when he was called away again to sea.

There had been no shortage of invites from well-meaning relatives since Mr Austen had died, so the ladies-of-no-fixed-abode planned another summer of visits while Frank and Mary arranged their wedding and went on honeymoon.

Before the women left Bath for good, they stopped off in Clifton, which was a recently built spa resort a few miles north-west of the city, sitting on picturesque high cliffs over a river. From there they went to visit Mrs Austen’s cousin, Reverend Thomas Leigh, in Adlestrop. He had welcomed them before, so they were sure of a warm reception. The timing was impeccable because, as luck would have it, their visit coincided with Reverend Leigh’s newly acquired inheritance of Stoneleigh Abbey. With so much to sort out with his lawyer it was imperative he attended in person, so he took the Austen ladies along with him when he went. It must have felt the equivalent of a royal palace for Mrs Austen, Cassandra and Jane compared to the run-down house they had just vacated in Trim Street.

Clifton

Stoneleigh Abbey

Edward Cooper's church of St Michael and All Angels in Hamstall Ridware.

Next stop was Staffordshire, where Mrs Austen’s nephew, Edward Cooper, lived in Hamstall Ridware. He and his wife had eight children, from a baby to a child of twelve, all of them having whooping cough during the time of their stay. The prospect of a long journey southwards to Southampton in October may not have seemed too daunting a prospect in the end, considering the circumstances!

Frank took lodgings for them all in Southampton, whilst they prepared the house that was going to be theirs; this was in Castle Square, on the border of the city walls and on the edge of the sea. Everyone contributed by making rugs, curtains, dressing tables and throws. The rooms were painted, and it was ready to move into by March 1807. Two months later, Mary, gave birth to her and Frank’s first child before the kind-hearted sailor was called again to duty in June, and sailed off to the Cape of Good Hope.

Site of the former house on Castle Square. The sea would have been up to the walls.

Everyone who had welcomed the Austen ladies as guests during their period of grief was invited to come and stay in Southampton, including a mix of different nieces and nephews who were growing up into fine young ladies and gentlemen in their own right.

Mary did not care for Castle Square as much as her husband did, so as soon as she had recovered from childbirth, she took her new daughter for a visit to Godmersham and then moved on to her family in Ramsgate. The following year she rented a cottage in Alton, leaving the house that Frank was paying for in Southampton to the exclusive use of his mother, sisters and their friend.

By all accounts, it was a happy time for them while they were there, with eccentric neighbours living in a gothic castle next door, and frequent trips to local beauty spots. They stayed there for two years, until a pair of properties became vacant on Edward Austen’s estates which he could offer them rent free. One was in Kent, near to Godmersham Park, and the other was in Chawton, close his manor house in Hampshire.

Jane Austen's House, Chawton

We all know the option Mrs Austen chose, taking her daughters excitedly to the cottage in Chawton in July 1809, known today as Jane Austen’s House.

At last, after five years of upheaval and uncertainty, the four ladies settled in a home of their own. It was to be where Mrs Austen, Cassandra and Jane would live out the rest of their lives, and from where Martha would leave to marry Frank and become his second wife. (Poor Mary had died giving birth to her and Frank’s eleventh child.)

The stability worked wonders for Jane and she was able to reawaken the creativity that had lain dormant since the days of her youth in Steventon. She could now devote herself once more to her writing and she did not disappoint. It was here in Chawton, that her greatest works were made ready for the world.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

House Hunting in bath

Published in Jane Austen's Regency World, Sept/Oct 2024.

It is well documented that when Jane Austen was told the news she was moving to Bath, she was not happy at the prospect. Her father was approaching 70 at the time, and her mother was 61. The rectory where they lived in Steventon had been home to a boarding school as well as a working farm; it was not unreasonable for Mr and Mrs Austen to decide it was too much for them to manage in their advancing years.

Mr Austen duly auctioned off his belongings and handed his church living over to his eldest son, James, in the spring of 1801. Only his two daughters remained under his care now, since all of his sons had already left home. There must have been part of him that hoped his girls would find a suitable husband each in Bath to secure their financial futures.

Right from the outset, the family wasted no time in considering the properties available. Within days of bringing in the new year of 1801, every available lodging up for lease in Bath had been scrutinised. Cassandra was staying with her brother, Edward, in Godmersham but her trusted opinions were still sought by letter. Jane wrote to her on the 3rd of January, setting out her findings of the different possibilities and urging her sister, ‘You and Edward may confer together, & your opinion of each will be expected with eagerness.’

On moving to Bath, the Austens resided in the first instance with Mrs Austen’s brother, James Leigh-Perrot, and his wife. It would have been nice to think they would all live close by one another as neighbours, and Mrs Leigh-Perrot certainly encouraged the idea. Jane wrote in the same letter, ‘We know that Mrs Perrot will want to get us into Axford Buildings, but we all unite in a particular dislike of that part of town.’

Photo: Axford Buildings, Bath

Axford Buildings was at the far end of the Paragon, where the Leigh-Perrots lived at No. 1. Although no explicit reason was given for disliking it, many historians have since speculated that it was likely due its distance from the centre of town, and the long walk up a steep incline to get there. It would have been difficult for the ageing Mr Austen to do this when he needed a stick to help him walk. Mr Leigh-Perrot often took a sedan chair to the Pump Rooms when he suffered with gout, but the Austens were not as affluent as him, nor were they as socially in demand.

The recognition that Axford Buildings was a possibility, however, does give us a starting point in trying to understand their budget. To work out the sums I have quoted in the rest of this article, I have taken the data from rightmove.co.uk.

In today’s world, the Leigh-Perrot’s Paragon townhouse sold for £700,000 in 2022. Axford Buildings was further along the road than that, in a direction away from town and in 2024 a single floor flat in the locality was advertised for £350,000. The Austens rented and did not buy outright, but if I were to seek out a similar styled property today my search filter would be set for around £700,000, with the hope that I could find something cheaper or at least negotiate on the fixtures and fittings.

The last time Jane had visited Bath before the permanent move was in 1799. On that occasion she had stayed in a rather nice house on Queen Square with her mother and her brother, Edward, and his family. We all know that Edward was affluent, and his aristocratic connections would have meant he was picky when choosing rooms: appearances mattered in Bath.

Mrs Austen remembered this holiday with fondness and so when a house came up for lease on the corner of Chapel Row and Princes Street, just a stone’s throw from where they had stayed before, it piqued Mrs Austen’s interest.

To the left is the house on Queen Square that Edward rented; to the right is the corner house that Mrs Austen favoured.

It was not pursued further, which must have been a relief to Jane who wrote diplomatically to Cassandra that their mother’s ‘knowledge is confined only to the outside’. Perhaps Jane was able to persuade her that the inside would not have been as appealing, because having done her homework Jane would have been very aware that this area of town was out of their price range. A five-bed terrace on Queen Square sold for £3 million in 2022 – a far cry from the house on the Paragon.

In Jane’s novel, Persuasion, Anne Elliot is faced with a dilemma when she learns her family are moving to Bath. Anne’s father, Sir Walter Elliot, is uncompromising in his demands that he must be situated in a good location. This was distressing for the practical Anne, who knew exactly what their financial situation was like. Surely, it is no coincidence that Jane Austen wrote this after her own father caused her a headache by craving somewhere far above his own limits.

She explained to Cassandra on the 14th of January, ‘He grows quite ambitious, and actually requires now a comfortable and creditable looking house.’ Laura Place was his favoured location, which Jane knew to be impossible. Her exasperation grew enough for her to continue to protest a week later, ‘I join with you in wishing for the environs of Laura Place, but do not venture to expect it.’ It is easy to see why - at the close of 2022, a 4- bedroom flat on Laura Place sold for £1.8 million - not even the whole house.

Laura Place

Trim Street

Trim Street was an uncomfortable option that could not be overlooked by the Austens. Its location was in the centre of town and the rents were very reasonable. They were some of the oldest houses in the city and the street itself was very narrow. The tall buildings stopped the fresh air from circulating and various businesses and inns were interspersed amongst the residential rooms. This would have meant constant noise and smells and it would also have been awkward to expect the well-respected Leigh-Perrots to be seen visiting them there. As early as January the family rejected it, with Jane informing Cassandra that their mother would ‘do everything in her power to avoid Trim Street’. Today, it sits much more proudly than it once did, and in 2023 a house being used as a business property there was advertised for £695,000.

Green Park Buildings West

If you walk a little further out of town beyond Queen Square, you come to Green Park. These properties are well proportioned and overlook a pleasant park. Such a situation was appealing to the Austens, understandably so when you consider they had come from the countryside. Two vacancies here caused a surge of excitement in May 1801. There were two rows of buildings around the fields: Green Park East and Green Park West. Two leases came up for renewal on the east side, and Jane wrote eagerly to Cassandra on 5th May, that ‘one of which pleased me very well’. She praised the size of the rooms and the bright aspect, only stopping short in her enthusiasm to admit that ‘the only doubt is the dampness of the offices, of which there were symptoms.’ The keen landlord offered to raise the floor for them in his eagerness to get their business, persuading them that it would lessen the effects of the damp. Jane continued to be keen, telling Cassandra that it was ‘so very desirable in size and situation,’ but in the end they did not take it. On the 20th May Jane wrote, ‘though the water may be kept out of sight, it cannot be sent away, nor the ill effects of its nearness be excluded.’

All of the buildings on the east side of the park were destroyed by bombs in World War II, but the mirror image on the west side still stands in part, to give us a good idea of what Jane’s property looked like. The cost of Green Park today is slightly more than the house on the Paragon, with a one storey flat on the street selling for just shy of £500,000 in 2023.

Charles Street

New King Street

Charles Street and New King Street were in the same locality as Green Park, and a little more towards the town centre away from the water. In 2023, a one floor flat in Charles Street sold for £175,000 and similar sized properties in New King Street sold for around £200,00. This figure would certainly have been appealing with regards to location and would also have been within the Austen’s budget. Their reason for rejection was revealed in Jane’s letter to Cassandra on the 5th of May ‘I was glad to hear my Uncle talk of all the houses in New King Street as too small; it was my own idea of them.’

After so much looking around and still finding themselves lodging with the Leigh-Perrots, things must have begun to feel desperate. Every area of the city had been scoured and nothing suitable had been found.

Jane and Cassandra enjoyed the attractions of Sydney Gardens and regularly walked there along Great Pulteney Street. New properties were sprouting up in the area all the time, so when Mr Austen saw a newspaper advert for a modern house at 4 Sydney Place, he lost no time in going to view it. The building boasted four storeys and a basement; it had a sunny drawing room with a large window overlooking Sydney Gardens. There was piped water, respectable neighbours and the landlord promised to give it a fresh coat of paint before they moved in.

Mr Austen signed up immediately, at last putting an end to the search. Whilst the landlord made the house ready, the Austens went on holiday to Devon, finally moving in during October 1801.

You can still play your own part in the history of Sydney Place today, as Number 5 up for sale as I write. It is a four-bedroom maisonette, priced at £625,00. Just think, a couple of hundred years earlier and Jane Austen would have been your next-door neighbour!

4 Sydney Place

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Human Connection

Published on the website of the Association of Self-Published Authors (ASPA) on May 21st, 2024. Find it here.

Sometimes the visions we see in our minds when we read are as real to us as the physical world we live in. I might argue that those imaginary worlds are often more appealing.

The same holds true when we think of the past. History lovers will tell you how rewarding it is to make sense of an old manuscript and how satisfying to apply their specialist knowledge to unfamiliar words.

For me, there is a ‘buzz’ to knowing the work was scribed by another human hand. It matters little in the end if a letter was read on the day it was posted or hundreds of years later. The fact remains that it has fulfilled its purpose in bringing a direct message from one mind to another.

Once upon a time every writer wrote by hand. Before the invention of the typewriter, they used pencils and pens. Before that, the basic quill and ink. There was no delete button to hide an unfortunate word choice in those days, so everything stayed on the page crossed out, for everyone else to see.

I found a very interesting webpage on buzzfeed.com showing a range of original manuscripts from famous writers. Each piece is different, and the personality of the writer shines out from the page. Take a look for yourself and see what they reveal to you about the person who wrote them: https://www.buzzfeed.com/alanamohamed/13-drafts-from-famous-authors-that-only-writers-can

It isn’t just me who gets excited about these kinds of things, either. The auctioneer Sotheby’s, recently listed an original handwritten manuscript of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of Four for a sum well over £1,000,000: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/arthur-conan-doyles-handwritten-sherlock-holmes-manuscript-is-for-sale-180984101/

Last year, a single page manuscript written by Dylan Thomas sold for over $10,000 at auction: https://www.rrauction.com/auctions/lot-detail/347935206760540-dylan-thomas-handwritten-manuscript-for-note-published-in-collected-poems-1934-1952

And a century old set of project books about cleaning, needlework and recipes sold for £950: https://www.lyonandturnbull.com/auctions/rare-books-manuscripts-maps-and-photography-549/lot/281

Such is the appeal of handwritten manuscripts.

If you are interested in books even further back, then Ziereis Facsimiles is an excellent site to visit. It presents hundreds of famous manuscripts dating right back to the 5th century, sought by collectors and libraries around the world. The original scripts and illustrations would all have been meticulously crafted by hand to reveal a wealth of information about contemporary life at the time: https://www.facsimiles.com/categories/the-special-ones/world-famous-manuscripts

I fully appreciate in today’s world we would be lost without digital technology. As time moves on, we must embrace what it brings and adapt alongside its change. But from a personal perspective, I still find something magical about a script written by hand; it brings the page alive and shows the mood of the writer in every stroke.

I recently volunteered to a museum seeking transcribers for a two-hundred-year-old journal. The appeal for help was so popular, that the website for applications was overwhelmed. I was one of the lucky ones and duly received my two pages to record exactly as it was written. From reading the posts of other lucky applicants to the project on social media, I could see they were all as excited to be part of the process as me.

It does make me smile though, to think of the person who wrote the journal in the first place. He could have no idea how it would be swooned over so many years later when he sat down to his laborious daily task!

The message I take from this reflection, therefore, is that we should never underestimate the value of our creations. Before you throw away those plot plans and mind maps you scribbled down last week, when you were too lazy to switch on your laptop, be warned that those are precisely the little things that may one day be worth a fortune.

All it takes is that some keen reader in the year 3000 will finally appreciate your genius and want to learn more about you!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Literature in School

Published on the website of the Association of Self-Published Authors (ASPA) on April 25th 2024. Find it here.

Always at this time of year, GCSE students up and down the country are being urged to remember key quotations for exams. ‘It will help if you can remember the important ones’ their teachers will say, and so they plough their way through snippets of Shakespeare plays and nineteenth century novels striving for the highest grades.

This request is in direct competition with the maths formulas they need to learn, along with multiple French verb tables and the dates of historical battles. The pressure on young minds is immense during exam season and it does not surprise me that some of them find English Literature a chore. Mutterings of ‘what’s the point’ ‘out of date’ and ‘boring’ are not unusual to hear, so teachers need a pretty strong case to prove it’s worth the effort.

Love of English

Here at ASPA it goes without saying that we are all avid readers and enjoy playing around with words but I wonder, if we never studied Literature as part of our own school curriculum, would we still have sought it out?

My own experience stems from primary school days when, around eight years of age, I won a poetry competition. It must have been organised by my teacher because I remember being taken to the library one evening to read my poem out in front of a group of strangers and was given a certificate by the mayor. My photo was in the local newspaper, and it felt like a big achievement. A couple of years later, I remember a creative writing lesson where the teacher lit a candle and we had to describe the flame; the next day she read mine out to the class. I can’t remember any other positive reinforcements like these in any other subject, so English was firmly secured as my favourite.

My inspiration to teach today comes from the fact that there will be other pupils experiencing a similar thing. Maybe their English teacher is the only one to praise their work, or perhaps for them a class trip to the theatre and being handed a copy of an old novel feels like a gift. Far beyond studying the obligatory character traits and themes that they need to to pass an exam, these students will have already discovered the pleasure of losing themselves in a good book or allowing a stage full of actors to inspire their imagination.

Difficult themes.

School texts also bring about the opportunity to discuss uncomfortable themes in a professional and neutral environment. In my lessons recently we have talked about rape, religion, drug abuse and disability in a way that would not be the same if I knew the individuals on a more personal level. We analyse quotations systematically, trying to understand the writer’s intentions in bringing these taboo subjects to light.

Students are encouraged to express themselves openly in written exams and describe the impression that certain words leave on them as readers. English Literature helps them to do this in a safe way and, as long as they can back up their arguments with sound reasoning, their opinion is as valid as anyone else’s. These skills give young people the opportunity to evaluate their thoughts and feelings on hard-to-talk-about topics in their own minds, even if they choose never to mention them again outside the lesson.

Memorable Quotes.

My yearly plea of ‘try to remember these few quotations at least’ is never met with enthusiasm, but I do inwardly smile in the knowledge that so many of these phrases will stay with the learners forever. For me, autumn continues to be the ‘season of mists and mellow fruitfulness’, and I have no doubt that many of my reluctant learners will surprise themselves one day by quoting a line from Shakespeare out of nowhere. ‘O, full of scorpions is my mind, dear wife!” is a particular favourite of mine from Macbeth.

Atticus’s line in To Kill a Mocking Bird is a common throw away response in class quizzes: ‘You rarely win, but you sometimes do,’ and there is definite distaste in revision sessions when readers recall the context of the ‘sweet young things’ from Robert Cormier’s Heroes.

If you know any sixteen-year- old studying the poem War Photographer, you can bet they know the line ‘The reader’s eyeballs prick with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers.’ Because, like everything else we read, there is a whole story behind a single line.

What of the future?

Nowadays, if a student tells me they can’t wait to burn their English books the minute the exam is over I might commend them on reaching such a decision. I will respect the fact they have made the choice of which subjects they want to pursue further and which ones they want to leave behind. But before the conversation is over, I will be sure to tell them to put their novels away in a corner instead of destroying them. ‘You never know,’ I will suggest, ‘You might want to read them again one day.'

Although they will laugh at such an outrageous idea, I still believe it to be true. Just as I can remember how to order sausage and chips in German (having never been to Germany in my life) I am certain that the time will come when a random quote from one of their literature texts pops into their heads without warning. That might be all it takes to tempt them to search out that book again.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

'It's no work for a woman!'

Published on the website of the Association of Self-Published Authors (ASPA) on April 11th, 2024. Find it here

In 1836, a twenty-year-old Charlotte Brontë wrote to the Poet Laureate of the day, Robert Southey, to seek his opinion about a poem she had written. His reply was kind, but pointed out in no uncertain terms that ‘literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life’ and her ‘proper duties’ were at home.

Charlotte was flattered that this revered figure of authority had taken time to reply, but his instruction also taught her an early lesson: female writers would always be met with bias and prejudice in her male-dominated world.

The Brontës lived in a quiet village in Yorkshire. Three sisters and a brother entertained themselves from a young age making up adventures with a set of toy soldiers, whilst their widowed father held the living of the church next door. The children created anthologies of poetry together and wrote tiny books of stories that required a magnifying glass to read them.

Photo right: This tiny book is about the length of my index finger and made from scraps of sugar paper and wallpaper sewn together by the sisters. It is on display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth, Yorkshire.

Photo: The signatures the sisters used as pseudonyms. On display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth.

Knowing their ‘unseemly’ pastime would be frowned upon, the sisters kept their writing a secret when they got older. They only submitted work to outsiders using pseudonyms and chose names that were ambiguous enough to be passed off as males.

Charlotte Brontë became Currer Bell; Emily Brontë wrote as Ellis Bell, and Anne Brontë was Acton Bell.

Their big breakthrough came in 1847. Drawing upon her memories as a governess and remembering two other sisters who had died from tuberculosis at school, Currer Bell wrote Jane Eyre. It received immediate acclaim for the London publishers Smith, Elder & Co. with critics in no doubt that this new author was male. No woman could possibly know about a man like Mr Rochester.

Meanwhile, Ellis Bell submitted Wuthering Heights, and Acton Bell submitted Agnes Grey to a different publisher, Thomas Cautley Newby, who printed the books together in a three-volume set.

Wuthering Heights baffled critics from the outset, who were shocked by its content. They accepted that it was imaginative, but most classed it as coarse, savage and cruel, even from a male author.

Little did these critics know, but Emily’s descriptions of Heathcliff were in fact inspired by her first-hand experience of watching her brother, Branwell, who was an alcoholic and opium addict. Her own solo ramblings across the wild and windy Yorkshire moors provided the setting.

Agnes Grey, based on Anne’s personal experience as a governess, was rather overshadowed in the outcry.

Photo: A portrait painted by Branwell Brontë of himself and his sisters. He later scrubbed out his own image. On display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth

Speculation grew about who these unfamiliar new authors were. Due to the fact they all shared the same surname, most critics thought they must be brothers. Some theorised there may be a husband and wife amongst them, and some wondered if they were actually one and the same person.

Charlotte recognised the time was right to reveal her true identity to her own publisher, Mr Smith, who was growing increasingly uneasy that Emily’s and Anne’s publishers were trying to share in the glory of Jane Eyre.

Photo left: A New York edition of Wuthering Heights, claimed to be written by 'The Author of Jane Eyre'. On display at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth.

All correspondence between Charlotte and Mr Smith had so far passed through the name of Currer Bell, so the man was very surprised when Currer Bell’s name was announced and in walked an unassuming, country woman wearing spectacles. Charlotte and Anne had travelled on purpose to London to introduce themselves to him, yet Charlotte still had to prove she was in earnest by showing him a copy of a letter written in his own hand.

He was said to be delighted at the discovery and eager to show off his protégé at the opera. The sisters, however, did not want their confidence betrayed, so to add another bizarre level to the deceit, Mr Smith introduced the ladies that evening as his country cousins, the Miss Browns.

1848 was a bad year for the Brontë sisters. First, their brother Branwell died, followed a few weeks later by Emily.

Anne had just published her second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall as Acton Bell, but this was considered even more shocking than Wuthering Heights. Reviewers did not like the plot which saw a mere woman leave her unfaithful and abusive husband. A year after publication, Anne also died.

Photo right: The home of the Brontë family, taken from the neighbouring churchyard. Haworth, Yorkshire.

Charlotte was now the only writer left, and keeping Currer Bell’s identity secret was no longer important to her. She had already told her father the truth by giving him a copy of Jane Eyre and revealed her literary exploits to a friend. Her brother (perhaps intentionally) had been the only one of the family never to have been made aware of his sisters’ true talents.

Photo: The rugged moorland landscape around Haworth.

Local residents recognised the settings in Currer Bell’s next novel, Shirley, and villagers began to gossip that Miss Brontë could be the author. Charlotte even suspected her post was being opened before it got to her in their attempts to prove their theories correct.

Her long and enduring friendship with her publisher, Mr Smith induced him to buy the rights of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, and he reprinted them for her in 1850, with a lengthy preface written by Charlotte giving full credit to her sisters for their work and revealing their true identities to the world.

Charlotte Brontë died in 1855, but her novels are still read widely today. The work of all three sisters have successfully endured the test of time, with Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights in particular being labelled as literary classics.

Not bad, I suppose, considering they were all penned by women!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How Do You Define Success?

Published on the website of the Association of Self-Published Authors (ASPA) on March 25th, 2024. Find it here.

Most of us strive to be successful writers, but what does that actually mean? Let me tell you the publishing history of Jane Austen, then perhaps you can decide if she would have considered herself a success or not.

Photo: Jane Austen Centre, Bath

Jane spent her teenage years writing outrageous and irreverent short stories. Epistolary novels were popular in her day, and at the age of 19 she drafted her first full length romantic novel, Elinor and Marianne, in this form.

In 1796, aged 20, she wrote another. This one was structured as a traditional novel with the title First Impressions. Her proud father approached a London publisher, offering to sell it for publication, but it was rejected by return of post.

In 1797 Jane went to Bath. She had never been there before, and her eyes were opened to an entirely new world. This inspiration went straight into her writing and a character called Susan was born, her third full-length novel.

Most of Jane’s family never really expected anything to come from this hobby and her manuscripts lay dormant in her writing desk. Girls in those days were raised for only one purpose, to marry and have lots of children and she did come very close. But fortunately for her, an older brother had connections.

In 1802, Henry Austen negotiated a deal with the publishers Crosby and Co. They bought the copyright of Susan for £10 which must have been a very exciting time for Jane. Unfortunately, Crosby never put Susan into print.

Six years later, and still unpublished, Jane never forgot this disappointment. She wrote an angry letter to Mr Crosby offering to send the manuscript again or take it elsewhere. He replied with an equally irate response, threatening he would put a stop to any other publication as, in fairness, he did still own the copyright. He conceded to sell it back to her for the same sum of £10, but Jane could not afford to buy it.

She continued to edit her earlier epistolary manuscript of Elinor and Marianne, revamping it now into a traditional novel with a new title, Sense and Sensibility. Henry took this to the publisher, Thomas Egerton, who accepted it on commission; Jane would keep the copyright in exchange for 10% of every sale and be liable to reimburse Mr Egerton for any copies left unsold. It published in 1811 under the pseudonym, ‘A Lady’, and proved to be the lucky break Jane Austen needed at the age of 35. Sense and Sensibility sold out within two years and earned a profit of £140 plus a second print run.

Photo: Jane Austen's House, Chawton.

Flushed with success, she next reworked First Impressions. Since she had originally written it, another book was out in circulation with the same title, so Jane was forced to change its name. She went for Pride and Prejudice. Mr Egerton offered her a lucrative £110 for the copyright and accredited it to ‘The Author of Sense and Sensibility’. It was big success but having given up her copyright, Jane saw none of this extra money. When two more print runs were released due to high demand, Mr Egerton kept the entire £465 profit.

Jane’s next work was longer and more serious. This was Mansfield Park which Mr Egerton did not like. He still agreed to publish it but was not interested in buying the copyright. It published in 1814 and sold out within six months, but still Mr Egerton refused a second run.

Photo: Jane Austen's Writing Table, Chawton

Jane Austen was on the crest of a wave at this point and ignored Mr Egerton’s professional advice. In 1815, she took her next novel Emma, to John Murray instead. On commencing business relations, Murray offered to buy the copyrights of Sense and Sensibility, Mansfield Park and Emma together for £450. Jane refused, choosing to publish Emma on commission and insisting upon a second print run of Mansfield Park.

This turned out to be another bad decision. Emma sold very well, but Mansfield Park did not. By the time she had covered her liabilities for the unsold books, she made only £39 on the whole project. Sadly, this was also her last experience of putting her novels into print. None of the four titles she had released had been credited to her name, and Mansfield Park had flopped.

She must have felt some consolation in 1816 when she finally bought back the £10 copyright of Susan from Mr Crosby, but even that was not without its problems. Similar to what had happened with First Impressions, another author now had the title Susan in circulation. Jane’s eponymous heroine needed a new name and thus became Catherine.

At 39 years old, Jane’s health began to fail. She persevered with her quill to complete one final manuscript, Persuasion, in 1816, and wrote the opening chapters to another story set in the fictional seaside resort of Sanditon. But none of these pages ever passed beyond her front door and in 1817 aged 41, she died.

In tribute to their sister, Henry and Cassandra Austen released Jane’s two unpublished novels soon after her death. Catherine was published with the new title Northanger Abbey, whilst Persuasion remained as it was. Henry took this opportunity to reveal his sister’s true identity as the author, but no mention of her literary achievements was ever made on her tombstone.

Original script of 'Sanditon' taken from www.janeausten.ac.uk/manuscripts

The copyrights to all six of her novels were sold off to a low-cost publisher in 1832, who marketed the outstanding copies still in circulation at rock bottom price. After that they went out of print altogether.

Over subsequent years, Jane’s manuscripts passed down through her family and the rest, as they say, is history. But for me this story serves as a reminder to us all: success and failure can come in many forms and are dependent on how they are perceived at the time. Not even the greatest and most famous of authors are immune from disappointment.

FOOTNOTE: If you would like to see the value of what Jane’s earnings were worth at the time, The National Archives has a currency convertor to show how many animals, stones of wool or quarters of wheat she could have bought with her money. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------